Social Security is an anti-poverty program successfully providing financial protection for decades for the nation’s citizens. The Social Security Administration (SSA) does a lot of things, but offering housing assistance to those with disabilities is not one of them. Thankfully, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) sponsors numerous programs that help vulnerable populations find and subsidize housing that meets their needs.

SSA does offer the Supplement Security Income (SSI) program, for those with financial need and no work history, and the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program, for those with a registered disability and a certain number of “work credits.”

Both programs provide monthly financial assistance, but the latter only assists candidates 18-65. This financial assistance does not solely target housing and therefore, it cannot be deemed rent assistance. Moreover, it’s an issue that strikes at the heart of fundamental American values: being financially independent and living alone.

In almost every culture but our own, multigenerational households are not sights to be ashamed of but recognition of the tight-knit nature of family. Mothers care for sons in their youth and in turn, grown sons care for their mothers in their elderly years.

In America, the former happens, but the latter does not: sons just stuff their mothers in retirement homes or just leave them to rot. A cynical view, yes, but what do those mothers do when the realization hits them, they’re on their own?

As mentioned, the Social Security Administration does not offer direct housing assistance, but two programs that deliver payments in the forms of monthly checks: SSI and SSDI.

Table of Contents

What is SSI?

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a needs-based program funded by general fund taxes and delivers monthly checks to candidates who may be blind, disabled, or elderly. It caters to those who have never worked or haven’t worked recently enough to qualify for SSDI.

However, it has very low income and asset limit stipulations, which make qualifying for the program nearly impossible for many.

The income limit is based on the federal benefit rate (FBR), which both sets the SSI income limit and the maximum monthly payment rate. As of 2018, this total has been set to $750 per month ($1,125), adjusted for certain exclusions.

A candidate’s monthly earned income cannot exceed $750 and this income is subtracted from the $750 package. Fortunately, the SSA never counts your full monthly income as monthly earned income, thereby opening up eligibility to a wider pool of candidates (“Understanding”).

What is counted as monthly earned income?

To make SSI available to those who need it most, the SSA defines monthly income in nebulous terms, not only including money earned from work, but also federal benefits, rent assistance, and income earned by household members. To continue qualifying for SSI, this total cannot exceed around $1,550 per month.

Besides payments earned from performing work, “unearned income” like Social Security payments, veterans’ benefits, pensions, alimonies, or child support is included in the total. Every month, $20 dollars of this “unearned income” can be subtracted from the monthly earned income total (“Understanding”).

Free shelter or food benefits from nongovernmental sources are also included in this total, including “in-kind” payments offered by friends or family. This money, though unearned, is money that would otherwise have been spent using earned income.

Finally, “deemed income,” or a portion of income earned by other members in a candidate’s household also contributes to the total. It is assumed that some of this money will contribute to a candidate’s welfare.

If the total of the preceding benefits exceeds $2,000 ($3,000 if married), SSI claimants will be ineligible for the program (“Guide”).

What are the exclusions?

Exclusions from the monthly earned income total include medical care, Social Security reimbursements, food stamps, and housing or home energy assistance.

Additionally, the first $65 of earned income and half of earned income past $65 is waived from the total. This makes calculating your eligibility much more complicated but opens up SSI to a wider pool of potential recipients (“Income”).

What about assets?

Assets are defined as any property owned by an SSI candidate that contributes to their material wealth.

To qualify for SSI, their assets cannot exceed $2,000 (if married, $3,000). These assets include cash, money in a savings account, cash value through life insurance, stocks/bonds and/or household items.

Exceptions to this policy include one car (as long as it is valued at less than $4,500), a principal residence (home), wedding rings and burial savings.

What about family income?

For SSI applicants or recipients living with parents or a spouse, a portion of family income is counted in the SSI income limit as “deemed” income (“Understanding”):

For children:

To determine payouts, the SSA “deems” parents’ income, unearned income (investments), and other assets if the disabled child is below 18 years, unmarried, and lives with parents who are not SSI recipients.

For married applicants:

As of 2018, if an SSI recipient’s spouse makes more than $375 per month and has no child; their income is subject to “deeming.” If the recipient has one child with the spouse, this monthly income allowance is increased to $750 per month (an additional $375 per child).

Domestic partnerships and civil unions are not recognized as legal marriages and therefore do not factor into “deeming.” However, relationships publically regarding as marital unions are counted.

In many cases, if a spouse’s income is high enough, an applicant will not qualify for SSI.

What are state supplements and how do they apply?

In addition to the monthly SSI payments, many states offer monetary supplements ranging anywhere from $10 to $400. This money is simply  added to the income limit in that particular state (e.g., a $200 state supplement to a $750 FBR makes the adjusted income limit and payment rate $950).

added to the income limit in that particular state (e.g., a $200 state supplement to a $750 FBR makes the adjusted income limit and payment rate $950).

Exceptions to this policy include the states of Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia, which do not grant state supplements (“Guide”).

Are there special eligibility requirements for new SSI applicants?

Yes, and in fact, when SSA evaluates first-time SSI applicants under 65, they will apply a separate earned income amount to determine whether an applicant is disabled.

Also known as “substantial gainful activity,” if an applicant’s work brings in more than $1,180 per month (or $1,970 for blind persons, who have significant impairment-related blind work expenses), the SSA will determine that that person is not disabled, but “able to engage in competitive employment.”

Those who exceed the $1,180 threshold may still receive SSI benefits if they have medical review to prove that they required special assistance at their workplace, were permitted to work irregular hours or take frequent breaks, were provided with equipment or other arranged circumstances, and/or were allowed to work at a less productive level.

Vocational experts, employed by the SSA, typically deemed a reduction of productivity by 15% a high enough margin to consider a claimant unemployable. Reasons for reduced productivity could include loss of concentration due to a medical condition or pain/fatigue.

On the other hand, those who earn lower than the $1,180 are not guaranteed impunity from an SGA violation. Disability applicants can be denied benefits if they are deemed to be capable of working more or for higher rates. The SSA reserves the right to consider volunteer and criminal activities as demonstrations of SGA if they are substantial enough to have been compensated for in another context.

If an applicant quits his/her work, they must provide evidence that it was due to a worsening medical condition. That is, their condition was exacerbated to the point where they could no longer engage in SGA. This is called an unsuccessful work attempt (UWA) and it is viewed as an excusable reason for reducing work or ceasing work activity altogether.

If work lasted less than six months, it is typically regarded as a UWA. Reasons for quitting could include doctor’s restrictions or an employer who removed special conditions for an impairment that had previously been tolerated. Work that lasts over six months cannot be treated as a UWA.

If an SSI recipient has been receiving benefits for more than one month, the SGA rule no longer applies and the recipient is free to exceed the $1,180 margin as long as they undercut the general income limit (“Substantial”).

What is SSDI?

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is a program funded through payroll taxes and is generally regarded as “insured” because they have completed years of work and contributed toward the Social Security Trust Fund in FICA Social Security taxes.

How do I qualify for SSDI?

Work history:

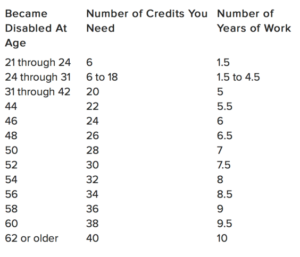

To determine eligibility through work history, the SSA converts earnings into work credits. As of 2018, $1,320 earns an applicant one Social Security work credit. They can earn up to four every year. Considering the minimal price for paying into Social Security, applicants must rake up a number of years before eligibility for SSDI, more the older the applicant is. The following chart provides the number of years/work credits needed to be eligible for benefits (“Benefits”).

Medical eligibility:

Recipients of SSDI must also demonstrate a disability that is severe, long-term, and total. This means that the disability must interfere with regular work, must be expected to last at least a year, and cannot allow recipients to perform SGA. Disability Determination Services (DDS) approves disability claims with a five-step verification process (Wixon et al.):

1. Financial screen

Applicants above the SGA limit are typically denied disability status because they are “not permanently and totally work disabled.”

Note: If a recipient of SSDI decides he/she wants to rejoin the workforce, they will be granted a few months of benefits in what is known as a “trial work period,” for them to assess their readiness for full reintegration within the workforce.

2. Medical screen

Applicants can be denied if their disability is deemed to not be severe. According to the SSA Program Operations Manual System, if the physical or mental impairment is a “slight abnormality or combination of slight abnormalities,” it is not considered severe enough to influence the applicant’s performance in the workplace.

The duration test is also used to determine if an applicant’s disability will either result in death or last at least 12 months. If so, the applicant moves on to step 3.

3. Additional medical screen

Disabilities are assessed under the Listing of Impairments, a codified clinical document listing over 100 impairments. If an applicant’s disability matches one seen in the listing, he/she is automatically approved. Additionally, if the applicant’s medical condition is deemed to “equal the Listing,” they are exempt from any further evaluation. However, if the applicant’s disability is deemed to require proof of severity outside of medical grounds, they must go through step 4.

4. RFC screen

In this step, applicants are evaluated based on residual functional capacity (RFC), or their competency in past and relevant work. The DDS looks into an applicant’s work history, as far back as 15 years, to determine whether they managed to meet the skill and task requirements for their previous jobs. Those who are determined to have met these requirements are denied disability claims. All others move onto the final step.

5. Additional RFC screen

The DDS then assess the applicant’s RFC in correlation to jobs other than those previously held by the applicant. They factor in the age, education, and work experience of the applicant to determine whether the applicant could be employed elsewhere according to their residual capacity. This determination requires the use of a vocational grid and medical-vocational profiles. This is often the clincher for many applicants and determines whether they will be granted disability claims.

Is there a waiting period before I receive my disability benefits?

Yes. In many cases, claimants may wait for up to five months before the SSA officially processes their request and begins payments (and back payments) for the recipient. This waiting period begins on the established onset date of the disability, as recognized by the SSA.

However, if a claimant has already been approved to receive disability benefits, they do not have to wait for the five-month period. Those who were approved for SSDI benefits, rejoined the workforce, and then became disabled again, are also not subject to the five-month waiting period (Laurence).

What are concurrent benefits?

If you are earning SSI and SSDI benefits simultaneously, these are called concurrent benefits. SSI monthly payments more often serve as supplements for SSDI. To qualify for these benefits, a recipient must be receiving less than $750 per month from SSDI.

SSDI also factors into the income limit eligibility for SSI. Those who receive SSDI often do not qualify for SSI because their unearned income is so high (“2018”).

What are some alternative housing options for seniors?

One of the most popular government-sponsored options is the housing choice voucher program, funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. It delivers housing assistance to low-income families, the disabled and the elderly. Seniors will find this program especially attractive because it allows them to select any single-family home, townhouse, or apartment within the private market that meets the requirements for the program. Moreover, they will not be cooped in subsidized housing projects (“Housing”). For more info on eligibility, see HUD.gov.

References

“A Guide to Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for Groups and Organizations.” 2018, www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-11015.pdf.

“Benefits Planner.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, www.ssa.gov/planners/disability/qualify.html.

“Housing Choice Vouchers Fact Sheet.” HUD.gov / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/about/fact_sheet.

“Income Exclusions for SSI Program.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/incomexcluded.html.

Laurence, Bethany K. “Social Security Disability Work Credits (SSDI).” www.disabilitysecrets.com, Nolo, www.disabilitysecrets.com/page10-13.html.

Laurence, Bethany K. “What Is the Five-Month Waiting Period for Social Security Disability?” www.disabilitysecrets.com, Nolo, 26 Apr. 2017, www.disabilitysecrets.com/five-month-waiting-period.html.

“Substantial Gainful Activity.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, 2018, www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/sga.html.

“Understanding Supplemental Security Income (SSI)– SSI Eligibility.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-eligibility-ussi.htm.

Wixon, Bernard, and Alexander Strand. “Social Security Administration.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, 1 June 2013, www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/rsnotes/rsn2013-01.html.

“2018 Red Book.” Social Security History, Social Security Administration, www.ssa.gov/redbook/eng/supportsexample.htm.